Cape Effect – How to prepare yourself for rounding a major West Coast cape

Pacific Yachting Magazine, November 2017

Tracing your fingers north to south along the undulating US west coast, you’ll notice several defiant projections, punctuating the surrounding coastline as it slopes south east and falls away to the Pacific Ocean. Cape Blanco, Cape Mendocino, Point Reyes, Point Arguello, Point Conception: the names of these giant capes have been long etched into mariner lore. Producing accelerated winds and harrowing sea conditions, their range of influence can stretch for hundreds of miles offshore. Needless to say they have caught many a sailor unaware, earning themselves a deserved reputation.

Sailing from Vancouver Island to Mexico in the fall of 2015 was our introduction to these notorious giants. Robin and I set sail from Ucluelet in our 1979 Dufour 35 on September 8th bound for San Francisco, our first multi-night offshore passage. On our 4th day at sea, 50 miles off of Coos Bay on the Oregon coast, the until-then pleasant conditions deteriorated.

We listened intently to the weather forecast, “Hazardous sea conditions are imminent or occurring. Recreational Boaters should remain in port…or take shelter until waves subside”. As the light fell, the wind and seas were building. Soon it was pitch black and the roar of white-water filled our ears. The cross sea produced 15-20 foot waves that successively threated to broach us. Wearing our survival suits and tethered to the cockpit we lurched forward when a roar from behind picked us up and turned us sideways, the cockpit filling with water. Our windvane was rendered ineffective and we spent the next 12 hours hand steering, fighting to hold our heading.

Once we’d passed Cape Blanco the wind abated, dropping from 25 to 3 knots in less than an hour. We were thoroughly exhausted and decided it was time to make port. We motored through a foggy calm into Eureka, Northern California, 270nm north of our original target. Somewhat rattled we were glad to turn our back on the blue horizon for a day or two and indulge in local oysters and craft beer.

As we cycled old town streets and wandered the giant redwood forests, our minds turned to the next big challenge, rounding Cape Mendocino enroute to San Francisco. The local fisherman had told us stories of her unpredictable nature, that with equal odds we might find ourselves plunging into a wretched cross sea, blinded by a thick fog, or motoring through calm and glassy waters. We were in no hurry to experience the former and wanting to give ourselves the best possible chance we opted to pay homage to the local weather oracles: The National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration’s National Weather Service (NOAA NWS). Their office was less than a 2 minute walk from the public dock in Eureka. We wandered up the docks and across the park, hoping to glean some weather wisdom for our imminent journey.

We arrived at the NOAA office, an unassuming building in a corner of the park, nestled amongst eucalyptus groves. Though we arrived completely unannounced we received a warm and friendly welcome. We were introduced to Troy Nicolini, Meteorologist-in-Charge and Mel Nordquist, Science and Operations Officer, who gave us a tour of the offices including a buzzing room with 5 analysts tracking weather on a dozen or so big screens, all alight with colorful satellite imagery and models.

Over the course of our visit Troy and Mel explained the Cape Effect and what we would encounter rounding Mendocino.

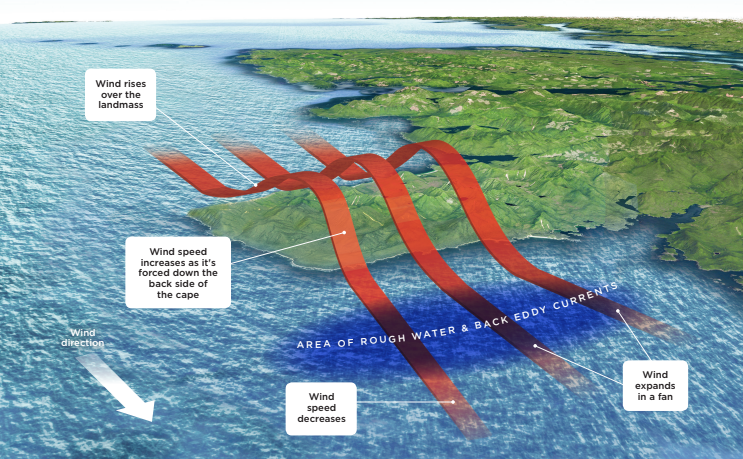

The Cape Effect (known in meteorology as an expansion fan) works in the same way as the wake in front of a boat. When the wind hits a cape a number of shock waves diverge from the corner. Each shock wave in the expansion fan turns the flow of the wind gradually around the corner. The wind velocity accelerates across the fan while pressure and temperature decrease. The lowered pressure near the center of the expansion fan causes an increase in down gradient air flow. Simultaneously higher wind speeds, aloft the headlands, are forced down to the surface. The combined result is a jet, or a core of stronger wind, parallel to the direction of the wind. Stronger winds build steep waves.

Another feature of Great Capes are the chaotic currents that can develop, sometimes described as eddies. These currents move in the opposite direction of the expansion fan wind and can steepen the already big waves that are resulting from the high winds. Mel, an avid sailor described a run-in with these conditions, “Rounding Mendocino we had 12 foot by 7 second waves with sloughing breaking faces. It was incredible. We would blast through the breaking waves and send spray pounding into the wheel house windows, and then plunge into the trough.“

Mel and Troy’s description felt chillingly familiar, had we experienced the Cape Affect off of Coos Bay? Given our description, Troy thought that, “Yes, that was very likely a cape effect event.” Feeling somewhat intimidated, we wondered if this was what we could expect from all of the capes down the coast, would they all be a hair-raising ride?

It turns out that these conditions can be found anywhere that a headland presents an obstacle to the wind, however the effect will vary from cape to cape due to differences in wind interaction with the terrain. Troy explained, “The terrain of each cape is unique to that cape and will cause variations in the wind field. Exactly how those variations will manifest themselves is beyond current modeling science.”

I asked Troy how we might be able to predict a cape effect, was there forecast data available for cape areas? He suggested that, “Mariners should not count on seeing the cape effect mentioned explicitly in standard text forecasts, just like they should not expect to see statements like ‘winds will be lighter near shore’. [Interpreting regional forecasts should be done] with some basic understanding of local effects, like that the friction of land often causes winds to slow down as they come on shore, or that a cape that protrudes out from the coast causes stronger winds from aloft to be pulled to the surface.”

However, Troy did mention that higher resolution forecasts might be useful, “As long as our forecasters are able to predict a local effect then it will be available through [point and click forecasts]. But do note that we can’t always forecast all local effects.”

We were keen to get Troy’s perspective as a sailor on rounding capes. What strategy was best? “Every cape is different,” he explained, “The best move is to talk to local professional mariners who transit the cape often. They can provide the best route and the best time of day to round a give cape.”

Troy received a buzz on his phone, there had been an earthquake in Chile and he had to go and investigate the potential for tsunamis along the coast. He told us to come back when we were within 24hrs of departure and that NOAA would provide us with a personalized forecast. We said a reluctant good bye, feeling immensely reassured with this new information and grateful to everyone at NOAA for their help.

Following Troy’s advice we spent the next couple of days consulting local fisherman on our dock, peppering them with questions on rounding Cape Mendocino. Their advice was to round at night and either stay in close (XXnm) or head far out (XXnm) to avoid the worst of the effect.

Armed with our newfound knowledge, we sailed competently (if not confidently) out of Eureka one late September afternoon. A few hours after crossing the Humboldt bar, we began our approach of Cape Mendocino. As the light fell and a velvety darkness enveloped us, we were pleased to find ourselves ghosting through placid seas. We had spent a week planning and waiting for weather, the cape looming ever present in the back of our minds. Finally we were rounding. We peered through the darkness, straining to catch a glimpse of the cape. All we could make out were shadowy contours, or perhaps even they were just a trick of the starlight. In a way it seemed only fitting that this formidable cape would remain obscured, the details of her magnitude and treacherous seas, happily left to our imaginations.